|

|

||||||||||||||||

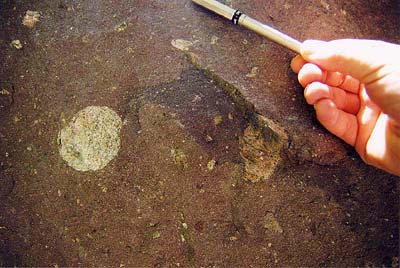

A model for the formation of this rock goes like this: imagine that the glaciers coming out of the nearby highlands encroached onto the edge of the lake. Glacial ice typically contains sediment of all sizes. At this point, the ice began to melt and the sediment, from the finest mud to the largest cobbles, fell out of the bottom of the ice onto the lake margin. (Another way this could have formed is from thick debris flows.) In this way, all the sediment would get deposited all in one place, raining out from the bottom of the glacier, with very little sorting or layering. The cobbles would be deposited in, and surrounded by sand and mud. There was apparently no later current to separate the cobbles from the mud or the sand. Thus, the cobbles do not touch (they are "matrix supported"), and we have our poorly sorted, unlayered rock. A model for the formation of this rock goes like this: imagine that the glaciers coming out of the nearby highlands encroached onto the edge of the lake. Glacial ice typically contains sediment of all sizes. At this point, the ice began to melt and the sediment, from the finest mud to the largest cobbles, fell out of the bottom of the ice onto the lake margin. (Another way this could have formed is from thick debris flows.) In this way, all the sediment would get deposited all in one place, raining out from the bottom of the glacier, with very little sorting or layering. The cobbles would be deposited in, and surrounded by sand and mud. There was apparently no later current to separate the cobbles from the mud or the sand. Thus, the cobbles do not touch (they are "matrix supported"), and we have our poorly sorted, unlayered rock.

This is fundamentally different from stops 1 and 3. At stop 1, the large cobbles touched, and all the grains were quite well rounded. There was very little mud in this rock. This is evidence of water washing through the sediment, as in a stream. At stop 3, the large grains were "matrix supported" like here. However, the matrix was layered with the varves that were described in stop 2. Thus, stop 2 represented dropstones in lake deposits. A couple of things need to be said about our lake. This lake was fairly large - the Konnarock Formation can be traced from the Tennessee border 45 km to the northeast through much of Grayson County with a total thickness of 1,100 meters of rock!!! The general trend is that the bottom of the formation appears to be dominated by the lake sediment itself - the layered muddy/silty rocks seen in stops 2 and 3. Higher in the formation the sandstones and diamictites take over, indicating that the trend was for the lake to fill in through glacial deposition, debris flows, or from stream channels entering the lake. Ultimately, the glaciers themselves advanced over the lake. How large were the glaciers? It is difficult to know for certain, but all of the cobbles seen here are derived from rocks found in the Mount Rogers area. Most of the cobbles are of the Cranberry Gneiss (light colored feldspar-rich rocks), and also of the maroon rhyolite. The Cranberry cobbles dominate, so the glaciers quite likely flowed off a granitic basement highland. Since all the cobbles are from local rock, the glaciers were probably small - otherwise known as "alpine" glaciers. How widespread was the glaciation? It is hard to give a definitive answer. Old glacial deposits, being land deposits, are inherently difficult to preserve. However, late Proterozoic glacial deposits from elsewhere in North America are known, so this might have been a time of significant cold climate, but these are the only glacial deposits known in the southeast from this time period. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

The grains are quartz pebbles that touch. The fact that they touch means that this is water reworked sediment that is in a fast-moving current, such as a gravel bar in a stream. We have seen this type of thing before in the sedimentary rocks of the lower Mount Rogers Formation. However, unlike the lower Mount Rogers, the fact that these are not feldspar-rich rock fragments of Cranberry Gniess or Mount Rogers rhyolite tells us that the landscape was probably lower and more eroded. Normally feldspar is a mineral that breaks down during stream erosion and transport, so that if you see a lot of it, that means the sediment hadn't travelled far - a fast, short transport in a rugged area. A lack of feldspar indicates a lower topography and longer transport. Thinking about our lake surrounded by glaciers in a mountainous area in the previous spot to what we see here, the landscape has certainly changed! In fact, we are now in the Unicoi Formation whose lower part is dominated by stream gravels and alluvial fans. There was obviously some relief around, as much of the lower Unicoi is an arkose (feldspar-rich sandstone), but it was not as rugged as the Mount Rogers Formation. The grains are quartz pebbles that touch. The fact that they touch means that this is water reworked sediment that is in a fast-moving current, such as a gravel bar in a stream. We have seen this type of thing before in the sedimentary rocks of the lower Mount Rogers Formation. However, unlike the lower Mount Rogers, the fact that these are not feldspar-rich rock fragments of Cranberry Gniess or Mount Rogers rhyolite tells us that the landscape was probably lower and more eroded. Normally feldspar is a mineral that breaks down during stream erosion and transport, so that if you see a lot of it, that means the sediment hadn't travelled far - a fast, short transport in a rugged area. A lack of feldspar indicates a lower topography and longer transport. Thinking about our lake surrounded by glaciers in a mountainous area in the previous spot to what we see here, the landscape has certainly changed! In fact, we are now in the Unicoi Formation whose lower part is dominated by stream gravels and alluvial fans. There was obviously some relief around, as much of the lower Unicoi is an arkose (feldspar-rich sandstone), but it was not as rugged as the Mount Rogers Formation.

There is a controversy about the contact that we just crossed: in places the Konnarock-Unicoi contact is knife-sharp, as if there was no break in the depositional sequence. However, the big environmental change indicates that some significant time may have elapsed between the two formations. What about the geologic time scale? The Konnarock is from the Proterozoic Eon, part of the Precambrian, while the Unicoi is Cambrian (a period in the Paleozoic Era) which is in the Phanerozoic Eon. We have just crossed an Eon boundary!!! |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

This is basalt. There are two basalt layers in here back behind the trees. The basalts are a characteristic unit in the middle part of the Unicoi Formation and they can be found from northeastern Tennessee to central Virginia. Thus the volcanism was quite widespread and geologists believe that this was associated with the rifting of the Iapetus Ocean. See the geologic history page for more details. This is basalt. There are two basalt layers in here back behind the trees. The basalts are a characteristic unit in the middle part of the Unicoi Formation and they can be found from northeastern Tennessee to central Virginia. Thus the volcanism was quite widespread and geologists believe that this was associated with the rifting of the Iapetus Ocean. See the geologic history page for more details. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

The rock is a white quartz sandstone. Look closely and see if you can't convince yourself that these are sand grains like you would see at a beach. The uniformity of the grain size and the purity of the quartz indicates that the grains are very well-travelled in terms of its length and time of transportation. The beds here exhibit some cross-bedding and ripple marks. This has been interpreted to have been deposited in an ocean setting, near the shore, under the influence of near shore currents such as tidal currents. At this point, the mountainous landscape seen in the Mount Rogers, Konnarock, and even the early part of the Unicoi are now eroded down to a much flatter topography. As you can see, the Unicoi Formation as a whole records quite a lot of geologic history. It starts as stream deposits, includes volcanic lava flows, and ends up in the ocean. This is called a "transgression" - a rise in sea level such that what was once on land (streams that flowed to the ocean) is eventually flooded by the ocean. The rock is a white quartz sandstone. Look closely and see if you can't convince yourself that these are sand grains like you would see at a beach. The uniformity of the grain size and the purity of the quartz indicates that the grains are very well-travelled in terms of its length and time of transportation. The beds here exhibit some cross-bedding and ripple marks. This has been interpreted to have been deposited in an ocean setting, near the shore, under the influence of near shore currents such as tidal currents. At this point, the mountainous landscape seen in the Mount Rogers, Konnarock, and even the early part of the Unicoi are now eroded down to a much flatter topography. As you can see, the Unicoi Formation as a whole records quite a lot of geologic history. It starts as stream deposits, includes volcanic lava flows, and ends up in the ocean. This is called a "transgression" - a rise in sea level such that what was once on land (streams that flowed to the ocean) is eventually flooded by the ocean.

Another big part of the geologic story is recorded here: the ocean these sands were deposited in was not the Atlantic Ocean of today, but the precursor ocean called the "Iapetus Ocean". This was the ocean that eventually closed when North America became part of the supercontinent of Pangea. The Iapetus Ocean survived for another 300 million years or so. Along the way, it became host to the reefs that formed the limestones of the Great Valley - but that is another field trip! One more note about these rocks. The fossil Rusophycus has been found here. These are trace fossils made by trilobites. They apparently liked to scoop out the sand and create resting places that are heart-shaped. Don't try to find them, though. According to Ed Simpson, the Unicoi Formation expert around here, they are exceedingly rare (of course, how did he find them???). Just food for thought... |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

| This is the Hampton Formation and it represents a deeper water, more offshore, and hence muddier, deposit on the Iapetus continental shelf. This continues the trend of the rise in sea level and the transgression. | ||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||