| ITEC 120 |

| 2007fall |

| ibarland, jdymacek |

|

|

|

home—info—exams—lectures—labs—hws

Recipe—Laws—lies—syntax—java.lang docs—java.util docs

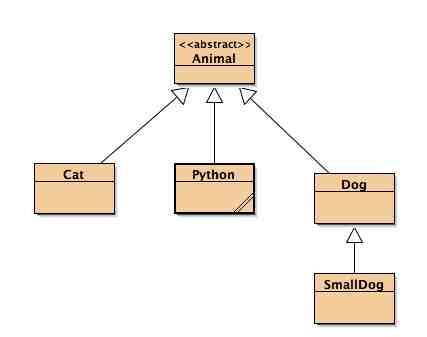

Inheritance: If class B extends A, we say “B is-a A”. Anything a A can do, a B can do too (and possibly more). For example, because Animals can speak, then automatically Dogs can speak.

Note that all fields and methods which are common to all subclasses are actually put inside of the superclass only once. That is, the code for speak and the field sound aren't repeated in each of Cat, Python, Dog, Narwhale, etc..

Mathematically: the set of Bs is a subset of the set of As.

polymorphism:

If a method takes a parameter of type A,

you can actually pass it a B if you want.

For example,

static String threaten( Animal attacker, Animal defender ) {

return attacker.speak() + defender.speak() + attacker.speak();

}

|

It's a straightforward concept, but it gets the fancy name “polymorphism” because it's the first time that we have an object which is constructed as one type (say, Python), yet declared as another (Animal). We sometimes speak of the object's “underlying type” and its “declared type”.

In fact, with polymorphism, we can have — for the first time — the fact that the “declared” type of a variable might differ from its “actual” type:

Animal a = new Dog( "Fido" );

java.util.List<Treasure> loot = new java.util.LinkedList<Treasure>();

|

(click for .jar)

(click for .jar) Observe that just because one class extends another, the superclass doesn't have to be abstract; certainly we can make Dogs which aren't some specific sub-class of Dog.

Abstract classes are used to represent “variant types”. (Although they aren't a total solution to this: while Animal does represent Cat-or-Dog-or-Python, you can't make a java type which corresponds to the variants String-or-Dog.)

Example: Suppose we want to sort a list of Treasures by weight (ascending). We write some complicated to do so (perhaps after taking ITEC 220); it will involve statements like

List<Treasure> sort( List<Treasure> items ) {

// ...code, perhaps including loops...

if (t1.getWeight() < t2.getWeight()) …

// ...

}

|

Then, later, we want to sort a list of Dogs, by age (ascending). This is practically the same problem; the only difference is that this version will involve statements like if (d1.getAge() < d2.getAge()) …. Yech! … nearly-repeated-code which is impossible to factor out because one deals with getWeight and another with getAge.

Interfaces, to the rescue! In particular, the the Comparable interface. If both Dogs and Treasures implement the interface, then our sorting code can include

if (e1.compareTo(e2) < 0) /* think: "e1 < e2" */ … |

code Dog implements Comparable<Dog> {

//... other Dog fields/methods

public int compareTo( Dog other ) {

if (this.getAge() < other.getAge()) {

return -1; // Any negative number is good enough to satisfy the interface.

}

else if (this.getAge() == other.getAge()) {

return 0;

}

else if (this.getAge() > other.getAge()) {

return +1; // Any positive number will suffice.

}

else {

System.err.println( "Shouldn't reach this far." );

return 0; // Better than returning a bad answer: Throw an exception.

}

}

}

|

Note that we don't want to have these two classes both inherit from some common superclass, each overriding compareTo appropriately. You might argue that perhaps class Object should've had including compareTo in the same way they already included toString and equals. However, there will always be new behaviors which people might want in the future, so having interfaces gives us, as programmers, a power different from abstract classes.

Another example: An example: Similarly, java.util.List is an interface, which is implemented by LinkedList, as well as a class named ArrayList.1 This means that if we change the signature String TreasureListToString( LinkedList<Treasure> loot ) to String TreasureListToString( List<Treasure> loot ) then our function will be able to handle both LinkedLists, as well as ArrayLists, as well as any other List variant people might invent in the future!

How to fake multiple inheritance, if Java doesn't allow it? That is, suppose we have Guard Dogs, which are like Dogs but they have some additional guard behaviours:

String threatenSound(); // How does this guard threaten? boolean deters(Animal anAnimal); // Does this guard succesfully deter anAnimal? |

But now we have the problem, that for a class GuardDog we want to Extend two different classes.

(click for .jar)

(click for .jar)

(click for .jar)

(click for .jar)

class GuardDog2 extends Dog implements IGuard {

private Guard guardDelegate = new Guard();

public String threatenSound() { return this.guardDelegate.threatenSound(); }

public boolean deters( Animal a ) { return this.guardDelegate.deters(a); }

GuardDog2() { super("Rex"); }

}

|

1 (Its name is a bit confusing; an ArrayList is not an array! It's a List, since it can get(index) and add and answer size() and isEmpty(). That is, it implements the List interface, so therefore an ArrayList is a List. You can't use square-brackets or the field length with ArrayList. It derives its name from the fact that under the hood, it uses arrays to help it organize its contents. But we don't care about how it works, as long as it meets its interface. ↩

home—info—exams—lectures—labs—hws

Recipe—Laws—lies—syntax—java.lang docs—java.util docs

| ©2007, Ian Barland, Radford University Last modified 2007.Dec.05 (Wed) |

Please mail any suggestions (incl. typos, broken links) to iba�rland |

|